Read time: 9 minutes

This article was written by Paul McCarney. It was published in Conservation Frontlines E-Magazine, January 1, 2020.

Our desire to tell hunting stories is an instinct that sits deeply in us. Through stories we convey values, teach moral lessons, entertain, pass on family and cultural traditions and communicate tacit knowledge. Our stories form a piece of the larger conservation narrative.

The environmental author Edward Abbey once said, “Hunting is one of the hardest things even to think about. Such a storm of conflicting emotions!” As we move our way through the hunting season, we acquire new stories to tell about the year’s successes and adventures. We will take and post photos on social media as a way to tell those stories. Many of us will grapple with the images and words we use to best represent these experiences.

This desire to tell our stories is an instinct that sits deeply in us. Humans are a storytelling species. Through our stories, we convey values, teach moral lessons, entertain, pass on family and cultural traditions and communicate tacit knowledge through metaphors.

The acclaimed ecologist Edward O. Wilson describes scientific naturalists as “historians, custodians of the stories each species will tell as its biology unfolds.” Hunters can fulfill this role as well, by using the same approach of carefully crafted storytelling to communicate our messages to the public and connect them to conservation.

The conservation narrative

When we tell a story, we often focus on an event that is localized in both time and space with a short-term outcome. For example, common hunting stories might be a description of our own hunt for one specific animal during a single day or season.

Narrative, on the other hand, refers to a larger collection of stories that convey a central meaning about an idea or theme. While related to the concept of a story, narratives also comprise and express the collection of values that inform the way we see and understand the world.

For instance, we might talk about the conservation narrative in North America. This larger, historical story about conservation includes the ugly history of unregulated hunting and wildlife decline; the characters who identified the threat and acted to create conservation organizations and articulate a new conservation model; and the legacy of that model that has continued to maintain healthy populations of wildlife for more than one hundred years.

In this way, our hunting stories collectively form a piece of the larger conservation narrative of this continent. Therefore, when we tell hunting stories, we participate in and contribute to the conservation narrative.

What is the power of narrative?

The historical importance of narrative in human cultures offers a lesson about the value and role of hunting stories in conservation.

In his book, I’m Right and You’re an Idiot, James Hoggan discusses the role of narrative in supporting positive public discourse and communication. He argues that, when used effectively, narrative can mobilize public support and action around an important issue.

Hoggan describes the work of sociologist Marshall Ganz, who believes that it is through powerful public narratives that people access the “moral and emotional resources” to take decisive action on important issues. According to Ganz, strong narrative skills can “deliver an inspiring message for change” and can also help reduce the polarization that characterizes much of public discourse.

Why narratives fail

Not all stories are created equal and not all stories will be effective in facilitating genuine communication and mobilizing public support. James Hoggan explores the use of narrative in a number of environmental campaigns and identifies why some public narratives fail to catalyze public action.

Public narratives fail when they rely too heavily on facts and do not resonate with people’s values and emotions. Of course presenting defensible facts is important, but it is not enough. We need to avoid conveying a sense of despair brought on by a deluge of vague intellectual facts. Effective public narratives are personal and inspiring. They move and empower people by presenting the possibility of a “mindful response to a challenge, as opposed to a fearful one.”

Narratives also fail when they are antagonistic or designed for shock value.

Effective narratives speak to the things that people care about without polarizing people.

These narratives become an “emotional dialogue that speaks about deeply held values, about an inspired future that is hopeful and steeped in those values.” If this all sounds somewhat abstract so far, Hoggan and Ganz also offer specific insight into the elements of an effective narrative and how we can craft our stories to capture the public’s attention and support.

The need for effective hunting narratives

As hunters, we understand how much meaning and emotion is wrapped up in a photo, a taxidermy mount or the story of a hunt. We are also very familiar with the polarization around hunting when the general public reacts to grip-and-grin photos or the notion of trophies. But we also understand how global biodiversity conservation needs regulated hunting.

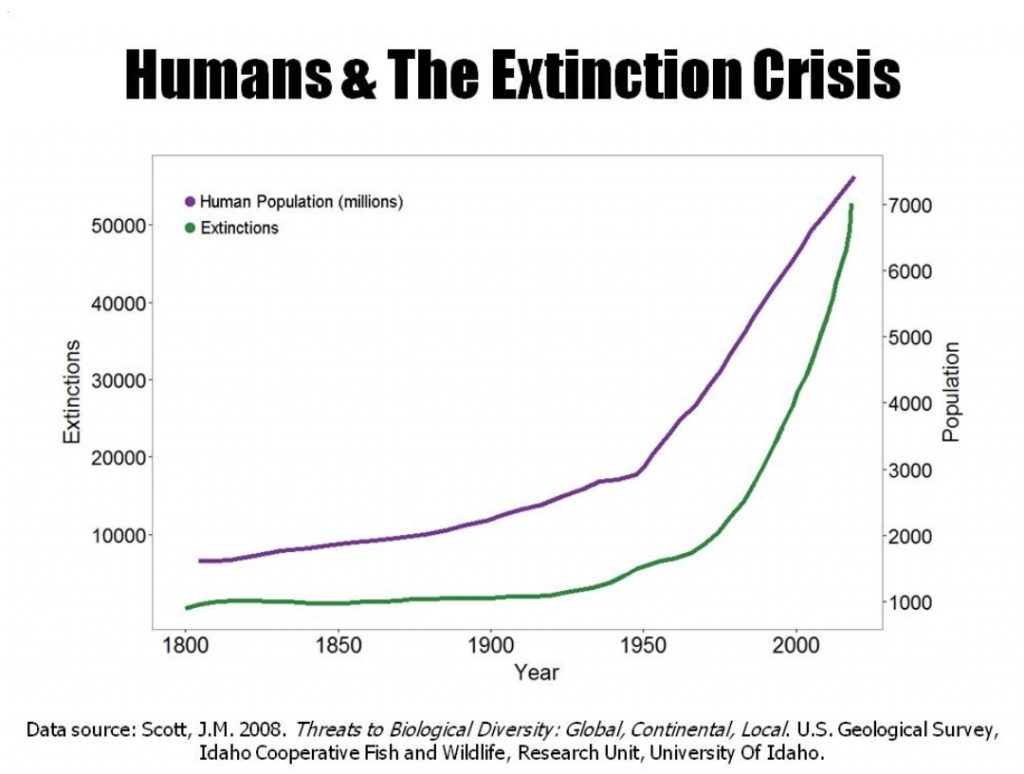

Global biodiversity is declining at an accelerating rate. The current rate of species extinction is somewhere in the neighborhood of one thousand times the pre-human rate. We desperately have to continue conservation efforts, and hunters are needed in those efforts. Public lands, species at risk and many other conservation issues need the revenue generated from economic activities associated with hunting, the volunteers and organizations working on the ground, and the biologists and managers who work tirelessly to manage wildlife populations.

At the same time, hunters also need the support of the general non-hunting, voting public to ensure that hunting continues to be a tool available to wildlife managers. One research studyfound that 87% of respondents support hunting for food.

So we need to frame a narrative that speaks to the values of the public and facilitates meaningful communication for the purpose of catalyzing conservation action.

However, if we allow the public to be increasingly polarized around hunting, we risk losing the support and understanding of the non-hunting public.

How do we meaningfully tell stories about such a controversial topic in order to enhance communication with the public and inspire conservation action?

Crafting the narrative

The key point in crafting a narrative is to remember the basic components of a good story. Our favorite books and movies resonate because they have inspiring characters and a moral message that stands the test of time.

Powerful narratives have a plot, characters and a moral.

To capture the public’s attention and sympathy, our narratives also must have these elements. Hopefully, we can then inspire the public to act by allowing them to identify with us, the characters, and our message, that of hope and unified action for the benefit of biodiversity.

The power of a public narrative is in its ability to identify a shared challenge; the choices that must be made to address that challenge; and an outcome that conveys a moral and creates positive change. According to Marshall Ganz, powerful narratives connect three broad components: a speaker’s story of self, a community’s story of us and the challenge’s story of now.

Strong narratives start with a story of self that articulates what inspires us personally, the values that call us to action. James Hoggan explains that people are often reluctant to tell their own story because we naturally fear that it is unremarkable, that “our own experiences are too trivial or don’t matter”—but that is not true. Our personal stories help people relate to us, and this is critical for effective communication. In summary, be personal.

Next, the story of us highlights the values that we have in common in order to establish a sense of shared experience. This part of the narrative connects individuals to a broader community that is committed to addressing the shared challenge. In terms of communicating with the public about hunting and conservation, this part of the narrative is critical. This is where we, hunters, attempt to break down barriers and connect with non-hunters through a shared value of biodiversity conservation and healthy wildlife. In summary, focus on shared values rather than ideology or facts.

Finally, a story of now turns the more individualized and localized aspects of the story into a narrative moment with a moral lesson. With the story of now, the group—at whatever scale it is conceived—takes on the challenge with a “mindful, intentional and strategic response.” As the storyteller, we have the opportunity to present the response and connect people to it. In summary, give people a positive action they can commit to.

Hunting stories as conservation action

What does all this mean for our individual hunting stories and the conservation issues we face in the world today? First, these lessons tell us that individual stories have power. It is important to remember that our own stories are part of a larger narrative. We can leave a legacy of responsible and meaningful participation in the conservation narrative by working to enhance true communication and inspire people to act. Second, we should tell our stories proudly and openly but sensitively and with the listener’s perspective in mind. We should not shy away from expressing the passion that underlies our desire to hunt and the emotions we experience while in the field. But we should avoid talking abouthunting in a manner that shocks or antagonizes non-hunters. Instead, express the values that motivate us to hunt and highlight the values that are shared by others. This will likely mean that we need to adjust the way we tell our stories depending on the audience, emphasizing certain aspects for a particular listener, and this is fine.

Finally, the lessons about public narrative can teach us that hunting stories, if used strategically, can be a way to catalyze conservation action. Hunters are well situated to bring personal stories of wildlife and their habitats to the public, but we need to do so in a way that inspires the public rather than exacerbates polarization.

Tell a good story!

As Hoggan tells us, “Good leaders understand a story must always be very specific and evoke a particular time and mood. It should be framed in a vibrant setting, with bright color, flavor and gritty texture.”

Some of the most renowned hunting writers and conservationists focused on these exact qualities in their stories. In his story of a turkey hunt in the Datil National Forest in New Mexico, Aldo Leopold vividly brings the reader into the scene when he tells of the “cold, frosty dawn,” the “hundreds of robins, bluebirds and pinon jays” and the way his knees were “wobbling like a reed shaken in the wind” at his first sight of a turkey.

After the story of the shot and the hike back to camp, he presents the reader with a critical conservation question: “By what device can we prevent the ‘cleaning’ of the hunting grounds?” With this, Leopold advocates for the importance of game refuges that can maintain an “irreducible minimum of breeding animals.” He brings us into the moment, enraptured with the landscape, and then seamlessly convinces us to care about taking action. Leopold, of course, inspired generations to create conservation areas for the protection of wildlife.

Of all the kinds of stories I know, hunting stories are perhaps most suited to capture and portray the color, flavour and grit of the magnificent landscapes we experience.

We all want to tell a good story, to captivate and entertain our audiences, and to pass on the most important lessons we feel we have learned through our experiences. When told well, those stories can help us encourage the public to care about conservation by connecting them to wildlife and wild places. So to other hunters out there, I say, tell your story. Tell it well and tell it meaningfully. And then listen.

Paul McCarney has a PhD in Environmental Studies; his thesis examined the social and ecological dimensions of wildlife research and management in the Arctic. McCarney lives in Nain, Labrador, where he is creating a marine management and conservation plan for Nunatsiavut called Imappivut. This article first appeared in Landscapes & Letters, a space created by McCarney to discuss issues and experiences in hunting and conservation.

Thank you, Conservation Frontlines, for permission to reproduce this publication.

Beitragsfoto: Felix Mittermeier auf pixabay

0 Kommentare zu “The Value of Hunting Stories for Conservation”